Muammar-al-Gaddafi's last minutes before he was Shot!

Contributed by: AllGov on August 22, 2011.

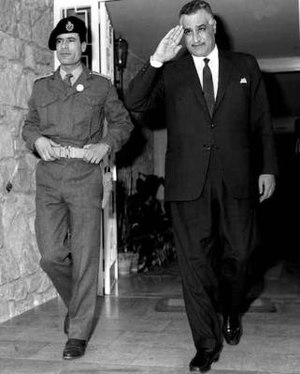

Image via Wikipedia

“All of the great prophets of modern times have come from the desert: Mohammed, Jesus and myself.”

-Muammar al-Gaddafi, October 1988

Muammar al-Gaddafi seized power in the North African nation of Libya in 1969 when he was only 27 years old. Finally, after 42 years, the Libyan people are on the verge of overthrowing him.

When I wrote my book,

Tyrants: The World’s 20 Worst Living Dictators, it goes without saying that I included a chapter about Gaddafi. Here is an extended excerpt from that chapter. I have eliminated the section on the history of Libya, but it can be found on the AllGov page on

Libya.

THE NATION—Libya is a North African nation of about 5,600,000 people of mixed Berber and Arab origin. Ninety-seven percent of the population are Sunni Muslims and 57% live in or near the three Mediterranean coastal cities of Tripoli, Benghazi, and Misratah. Libya, a mostly desert country, is a player on the world scene because of its high-quality petroleum reserves. Internationally, Libya is probably less well known than its leader, the notorious dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi.

THE MAN—Muammar al-Gaddafi appears to have been born in 1942. His family were members of the Qathathfa tribe, Arabized Berbers who were exiled from Cyrenaica. According to Gaddafi, his grandfather was killed fighting the Italians and his father was wounded during World War I. The family were Bedouin nomads who lived in tents and made their living growing barley and trading livestock. The youngest of six children and the only son, Muammar was the pet of the family, and he received an abundance of loving attention. When he was nine or ten years old, his father sent him to school for the first time in Sirte, a town of 7,000 people. He slept in the local mosque and went home to visit once a week, after traveling the thirty kilometers each way on foot. As one of only three or four Bedouin at the school, he was treated with contempt by some of the other students.

When Muammar was fourteen years old, his family moved to the Fezzan, where he attended the Sebha Preparatory School. It was here that he became best friends with Abdel Salam Jalloud, and the two would share a remarkable life’s journey. During this period, Gamel Abdul Nasser of Egypt was promoting Arab pride and Arab unity, and the young Gaddafi was greatly moved by Nasser’s message. His most prized possession was his copy of Nasser’s Philosophy of the Revolution. Gaddafi was seventeen years old when he first began dreaming of leading a revolution in Libya. At school he led demonstrations to protest the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, to protest the French testing of atomic bombs, and in favor of the anticolonial revolution in Algeria. He was finally expelled from school for distributing photographs of Nasser. After attending school for two more years in Misratch, Gaddafi enrolled, in 1963, in the Military Academy in Benghazi. This was a calculated decision based on his realization that to achieve a successful revolution he needed to control the military. Gaddafi convinced friends of his, including Abdel Salam Jalloud, to enter the Academy as well. Gaddafi distrusted older officers and he concentrated on men his own age when he created the Free Unionist Officers, a group devoted to the goal of Arab unity. Gaddafi graduated in 1966 and then spent several months in Great Britain at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

THE 1969 COUP—By 1969, Gaddafi and his friends were ready to stage their coup. Gaddafi took advantage of the six weeks’ leave he had accumulated and set the date for the takeover for March 12. However, it turned out that the legendary Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum was scheduled to perform that night. Her concerts lasted hours. All of Libya’s political and military leaders would be there all night with their families. Out of respect for Kulthum and wishing to avoid the awkwardness of arresting the leaders in front of their wives and children, Gaddafi postponed the revolution. After another false start a couple weeks later, the coup was rescheduled for August 13, when the entire Army High Command would be together, attending a conference on the importance of air defense. However, Gaddafi’s supporters felt they were not yet prepared to seize control of important army units in Tripoli, so the takeover was aborted again. Finally, on September 1, they were ready. At the time, Libya’s army consisted of 6,000 men. There was also a small naval force, a small air force stationed at the Americans’ Wheelus Field, and police and security forces numbering about 12,000 men.

At 2:30 a.m., Gaddafi and his followers made their move. By 4:30 they had successfully taken control of the military and the country without killing a single person. It says a lot about King Idris’ lack of popularity that seventy young officers could overthrow the government in just two hours in a nearly bloodless coup.

A year later, Gaddafi and four of his associates celebrated the first anniversary of their coup by appearing on television and relating the details of their memorable night. Their tone was that of a bunch of fraternity brothers describing an elaborate prank, as they described stopping at an Italian-owned café for brioches and milk on their way to the revolution, losing control of one of their cars and running into each other, and so on.

IN POWER—At the age of twenty-seven, Muammar al-Gaddafi joined the ranks of world leaders. At 6:30 a.m. on September 1, 1969, he appeared on national radio and announced that henceforth Libya would be “a free, self-governing republic.” Departing from his prepared text, he tried to reassure foreigners living in Libya that there would be no threat to their lives or property and that “our enterprise is in no sense directed against any state whatever.” Gaddafi appointed himself commander-in-chief of the Libyan Armed Forces, while his best friend, Abdel Salam Jalloud, became deputy prime minister (within three years Jalloud would move up to prime minister). This was heady stuff for Gaddafi: to dream of leading a revolution at the age of seventeen and then pull it off only ten years later. And, unlike most coup leaders around the world, Gaddafi, thanks to Libya’s oil reserves, had the resources to carry out some of his more fanciful plans.

Six weeks after seizing power, Gaddafi announced his five major goals:

1. removal of foreign military bases

2. international neutrality

3. national unity

4. Arab unity

5. suppression of political parties

By the end of his first year in power he had achieved four of those five goals. The bases were gone, he had staked out a position between the two superpowers in the Cold War, and he had most definitely suppressed all political parties. In a country with little history of political involvement, it was easy to achieve a rough approximation of national unity: Gaddafi nationalized the banks, raised the price of oil for foreign companies, and doubled the minimum wage. Achieving Arab unity was another matter, and it would prove to be a frustrating obsession that would dominate the rest of his life.

ARAB UNITY—Gaddafi had been deeply moved by what he viewed as a humiliating defeat of Arab armies by Israel in 1967. Inspired by the speeches of Nasser, he hoped to galvanize the support of other Arab leaders to gain revenge against the Jewish state. When Gaddafi made his first tour of Arab capitals in 1970, he was shocked that his calls for revenge met with tepid responses. Nasser himself was pleased to have a highly placed disciple, but he died only a few months later. The other leaders were annoyed that Gaddafi, a young upstart from a country far from the fighting, should lecture them as to what should be done. They found him not so much arrogant as naive. Yet Gaddafi was sufficiently piqued to support the Palestinians in their revolt against the king of Jordan. On February 21, 1973, Israel shot down a Libyan commercial airplane that strayed into the Israeli-occupied Sinai, killing 106 civilians. During the next war with Israel in October 1973, Gaddafi donated Libyan planes to the Egyptian air force. When Anwar Sadat, Egypt’s president, agreed to a ceasefire with Israel, Gaddafi accused him of cowardice.

Between 1971 and 1980, Gaddafi made repeated attempts to unite Libya with various Arab countries. There was much talk of solidarity and occasionally papers were signed, but Gaddafi was always frustrated in his attempts to achieve a substantive union. In 1977 he actually fought a brief border war with Egypt, and in 1995 he threatened to expel 30,000 Palestinians from Libya to protest the Oslo Peace Accords signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. (He suspended the program after expelling 1,500.) In 1984 he randomly laid mines in the Red Sea, disrupting traffic and severely damaging the Egyptian economy. Meanwhile, Gaddafi was showing increasing interest in Africa, a continent filled with leaders in need of the money Gaddafi was prepared to dole out. In 1998, Gaddafi changed the name of the national radio station from Voice of the Arab Nation to Voice of Africa. In 2003, at an Arab League summit to discuss the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq, Gaddafi engaged in a public exchange of name-calling with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Abdullah that was broadcast on television. Gaddafi announced that he was withdrawing from the Arab League and that Libya was “above all an African country.”

GOVERNMENT BY CHAOS—When, in 1972, the Libyan parliament began pushing for democratic reforms, Gaddafi was not pleased. Declaring that “representation is fraud,” he proposed that he would bring to the Libyan people a purer form of democracy than the ones available to citizens in the West. Vaguely inspired by China’s Cultural Revolution, Gaddafi created a system of “popular committees.” The idea was that in all institutions, including businesses with two or more employees, the workers would elect their own people’s committee to run the show. “Everyone is on an equal level,” said Gaddafi, “the director general with the simple worker.” Commercial enterprises would also give up 50% ownership to the workers. Of course there was one catch to this new form of radical democracy. As Gaddafi explained, “I shall have the right…to tell the elected popular committees that they have not expressed the general will in a suitable manner, or they have not acted as they should in some way.” In other words, Gaddafi retained veto power over every decision made by every popular committee.

Eventually, despite the restrictions, the popular committees became too independent for Gaddafi. In 1977 he created a new layer of control: the revolutionary committees, the members of which were chosen from zealots who responded to his speeches. Their job was to “guide” the popular committees and to identify for punishment anyone who engaged in “deviation” or “opposition.”

In time, Gaddafi became dissatisfied with the revolutionary committees as well. He criticized them for being arrogant and corrupt—and for having long hair and wearing jeans. In 1995, Gaddafi added yet another level to his bureaucracy by creating 250 “cleansing committees” to weed out “counterrevolutionaries.” Gaddafi’s definition of counterrevolutionary is broad; at one point a cleansing committee arrested a Palestinian for selling “Israeli aphrodisiac gum.”

CHAIRMAN OF THE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE—Respecting human rights has never been one of Muammar al-Gaddafi’s strong points. At various times during his thirty-seven-year reign, he has:

· Redrawn administrative boundaries in order to disrupt natural tribal boundaries

· Imposed the death penalty for belonging to a political party other than his own

· Imposed the death penalty for speculation in currency, food, clothing or housing

· Imposed the death penalty for alcohol-related crimes

· Expelled Italians and Jews and confiscated their property

· Launched a “Green Terror” against Marxists

· Held political trials in secret

· Forbidden the ownership of more than one private residence

· Shut down Islamic schools

· Punished those who refused to reveal the details of their personal wealth by having their hands chopped off

· Punished robbers by having their right hand and their left leg amputated

In 1997, Gaddafi ordered the People’s Congress to pass a collective guilt and punishment law. According to this unusually appalling regulation, an entire family, tribe, village, or town can be punished if a single member helps, protects, or merely fails to identify a perpetrator of a “crime against the state.” Included in the definition of such crimes are “practicing tribal fanaticism,” possessing an unlicensed weapon and the all-inclusive “damaging public or private institutions or property.”

Considering this record of abuse, the United Nations hit one of the low points in its history when, in January 2003, Libya was chosen to chair the UN Human Rights Commission. How could this have happened? Gaddafi exploited a loophole in the Commission’s rules, whereby each continent takes its turn in leading the Commission and the chair is chosen by the members of the continent itself. As the turn of Africa approached, Gaddafi went to great lengths to financially reward the leaders of African nations in order to win their votes. For good measure, he announced the release of political prisoners except “a group of heretics who are believed to have links with what is known as al-Qaeda and the Taliban.” In a jab at the United States, he noted that these prisoners would be treated in the same manner as those the U.S. was holding in Guantánamo Bay. “These people do not have the right to defend themselves; we will never provide them with lawyers, nor will their human rights be respected.”

TERRORISM—In 1979, Gaddafi warned opposition leaders living abroad that they must return home or face “liquidation.” True to his word, over time Gaddafi would see to it that Libyan intelligence officers assassinated about two dozen Libyan exiles. During an anti-Gaddafi demonstration in front of the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, a Libyan intelligence operative mistakenly shot to death a policewoman named Yvonne Fletcher. Besides targeting his own opponents, Gaddafi gave money to various Islamic liberation and terrorist groups, most notably the Palestinian group headed by Abu Nidal. Still, when Ronald Reagan took power as president of the United States in 1981, Gaddafi was not an active participant in terrorism and even his support for terrorist organizations did not compare to that of Syria or, later, Iran.

Yet Reagan, almost from the day he took office, chose Gaddafi as his favorite enemy and set about provoking him. Reagan negotiated with Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union, provided arms to Iran, and turned a blind eye to Syria’s support for terrorism. But for Reagan, it was Gaddafi who was the perfect enemy: he was obviously a tyrant, he was widely viewed as weird, and Libya, although wealthy, was a small country with an ineffectual military that lost a war to Chad. Since Gaddafi’s actual behavior was often strange and erratic, it was easy to spread outrageous rumors about him. For example, in 1981, the Reagan administration declared that Gaddafi had outfitted “special assassination squads” to kill President Reagan and members of his cabinet, stirring a brief moment of national hysteria, although William Webster, the Director of the FBI, said in an interview weeks later that the existence of such squads had never been confirmed. After his reelection in 1984, Reagan revved up his campaign against Gaddafi to include actual violence. The Americans prepared a plan called “Rose” that included an attack on Gaddafi’s personal barracks. In March 1985, the U.S. military carried out maneuvers off the coast of Libya and challenged Gaddafi’s version of the dividing line between Libyan and international waters. There was an exchange of fire and the U.S. sank two Libyan patrol boats in the Gulf of Sirte, killing seventy-two sailors. The Americans also conducted bombing raids against radar and missile installations. In December 1985, Abu Nidal launched terrorist attacks at the Rome and Vienna airports. The Reagan administration blamed Gaddafi for backing the attacks, although U.S. intelligence reports suggest that the Syrian government was more involved than the Libyans.

On April 5, 1986, a bomb went off at the La Belle disco in Berlin, a night spot frequented by U.S. soldiers. Three people were killed, two of whom were American soldiers, and 229 people were injured, including 79 Americans. A few days later, the U.S. government announced that it had intercepted communication that implied that the La Belle bombing had been organized by members of the Libyan secret service operating out of the Libyan embassy in East Berlin.

In the early morning hours of April 15, forty U.S. warplanes based in Great Britain flew over Libya and bombed a barracks in Benghazi, a naval academy, a frogman’s training school, and a camp for training Palestinian guerrillas. However, it was the final site that the Americans bombed that attracted international attention: Gaddafi’s personal compound at the Didi Balal naval base. Flying only 200 feet above the ground, the U.S. fighters dropped 2,000-pound laser-guided bombs on Gaddafi’s residence. Remarkably, although they badly damaged his tennis courts, they missed Gaddafi, who was in his command center deep underground. The Americans did kill Gaddafi’s eighteen-month-old adopted daughter and injured two of his sons. In all, 101 people were killed.

In a bizarre twist, supporters of Ronald Reagan would hail the attack as a high point of his presidency, a demonstration of how terrorists should be dealt with. To this day there are Reagan admirers who declare that, “we never had to worry about Gaddafi again after that.” Unfortunately, the exact opposite was the truth. According to figures provided by the U.S. Department of State, in 1985, Libya was involved in fifteen acts of terrorism, twelve committed by Abu Nidal’s group. In 1986, the number jumped to nineteen acts against non-Libyans, and Gaddafi for the first time began targeting Americans. A planned attack in New York in 1988 failed when a terrorist carrying bombs was stopped for a traffic violation in New Jersey. But then, on December 21, 1988, Gaddafi got his revenge against the United States when a bomb destroyed Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 270 people. On September 19, 1989, Gaddafi also gained revenge against the French for their support of the Chadian military rout of Libyan forces by blowing up UTA flight 772 over the Sahara Desert, killing 171 passengers and crew.

The Americans and the French demanded that Gaddafi turn over the perpetrators of these two crimes. When he refused, the United Nations imposed an air embargo against Libya and then froze Libyan funds held in other countries. The UN also banned the sale of equipment to Libya that could be used for oil or natural gas operations, although the sale of petroleum was allowed to continue. These sanctions gradually took their toll on the Libyan economy. In 1996, Gaddafi agreed to let a French investigative judge come to Libya and search the offices of the Libyan intelligence services. Miraculously, the judge found a suitcase just like those used in the bombing. The French convicted six Libyans in absentia including Gaddafi’s brother-in-law. In 1999, Gaddafi, in exchange for the lifting of UN sanctions, turned over to authorities two suspects in the Lockerbie case, Abdelbaset Ali Mohamed al-Megrahi and Al-Amin Khalifa Fhiman. A Scottish court, operating in the Netherlands, held an eighty-four-day trial that culminated in the conviction of al-Megrahi. Fhiman, on the other hand, turned out to be nothing more than an employee of Libyan Arab Airlines and he was acquitted. Gaddafi paid compensation to the families of the victims of both bombings, all sanctions were lifted, and oil companies and others enthusiastically recommenced business with Libya. As for the La Belle disco attack, after a four-year trial, in November 2001, a German court convicted two Libyans and a German woman, Verena Chanaa, who was charged with actually planting the bomb. Gaddafi himself escaped prosecution because the U.S. and German governments refused to share intelligence with the prosecutors.

BIZARRE BEHAVIOR:

- Gaddafi has a long record of disappearing from public view without warning. The first instance occurred in 1971 when Gaddafi went missing for sixteen days and failed to show up for a meeting in Cairo of the Presidential Council of the United Arab Republic. He suddenly reappeared and the meeting went ahead, although six days late. He also missed the celebration of the fourth anniversary of the Revolution, and the President of Tunisia, Hassib Bourguiba spoke in his place.

- Gaddafi is protected by a coterie of high-heeled female bodyguards known as the Green Nuns. One of them reportedly died when she took a bullet during a 1998 assassination attempt.

- In 1977, Gaddafi ordered all Libyans to raise chickens, even urban dwellers who lived in apartments.

- His speeches often include conflicting ideas, and the nation is forced to wait for written clarifications before policies can be carried out.

- He has been known to lie on the floor of his office, covered by a sheet, for up to two hours at a time.

- Gaddafi became so well known for making passes at female journalists that Western media outlets began sending their most attractive reporters to Libya in order to gain access to him.

- Imelda Marcos, the First Lady of the Philippines, made two trips to Tripoli to try to convince Gaddafi to stop funding Moro insurgents in the southern Philippines. The two got on well and, after Imelda’s second visit, Gaddafi stopped the funding.

- Inspired by Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book, Gaddafi compiled his philosophy into the Green Book. In the tent he used for entertaining guests, he had his favorite thoughts from the Green Book embroidered into the fabric of the walls.

- He also had his thoughts put to a disco beat and broadcast as music videos on Libyan television. Among the catchy lyrics from the song, “The Third Universal Theory”:

The universal theory has seen the light,

Bringing mankind peace and delight,

The tree, oh, of justice, people’s rule and socialism,

Completely different from laissez-faire and capitalism,

Based on religion and nationalism.

- Gaddafi invited IRA recruits to terrorist training camps in Libya. However the recruits returned early to Northern Ireland when they discovered that they were being taught how to fight in the desert, a skill that was not terribly useful on the Emerald Isle.

- In the words of Jaafar Nimieri, former president of Sudan, Gaddafi “has a split personality…both evil.”

QUOTES:

“We burned no books in Libya. We simply withdrew certain books from the libraries and bookshops.”

1974

“The Libyan Arab people have existed for hundreds of years without oil and are capable, if necessary, of living without it for many more centuries.”

1975

“American soldiers must be turned into lambs, and eating them is tolerated.”

June 15, 1986

“We must recognize that we are very far removed from the precepts of Christ, and that we are very close to the designs of Satan….We need to read again the teachings of Christ and to find in them the voice which says to us, ‘Give up Palestine, Southeast Asia, Ireland, Germany, and the African colonies…The World needs Christ again.’”

January 1, 1975

“Political struggle that results in the victory of a candidate with 51% of the vote leads to a dictatorial governing body disguised as a false democracy, since 49% of the electorate is ruled by an instrument of governing that they did not vote for, but had imposed upon them. This is dictatorship.”

The Green Book

“All of the great prophets of modern times have come from the desert: Mohammed, Jesus and myself.”

October 1988

-David Wallechinsky

there we will not be challenged, experience personal growth, or learn new and exciting things.

there we will not be challenged, experience personal growth, or learn new and exciting things.